It was a “yes” that so many women weren’t sure would ever come. And now that it was here, the question for Jenny Boucek, and so many others, was, “What are you going to do with it?”

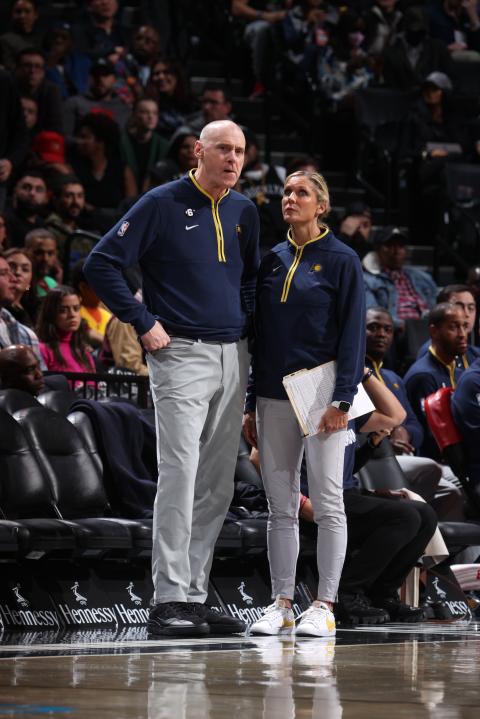

The year was 1997, and female athletes were beginning to reap the very tangible benefits and opportunities provided by Title IX, the law ensuring entities receiving federal financial assistance couldn’t discriminate against individuals based on sex. The Women’s National Basketball Association was playing its inaugural season that summer and Boucek, now an assistant coach with the NBA’s Indiana Pacers, remembers those early WNBA games vividly.

“[Games] would be sold out and grown women would be in the stands in tears because of what they had been through,” Boucek remembers. “All the ‘nos’ they had received because of their gender. The WNBA represented a ‘yes,’ and a big ‘yes,’ not just basketball but [that] women can do things they’ve never been allowed to do.

“You can see little girls in the stands almost confused, like, ‘Wow, I didn’t think women could play basketball professionally.’ Even seeing the little boys in the stands with jerseys on and cheering for women, it was like, ‘Okay, this is going to raise up a generation of boys that will grow up into men who respect women differently – their wives, their daughters, their colleagues.’”

It was the start of something big, and every player on those eight teams in that inaugural season could feel it.