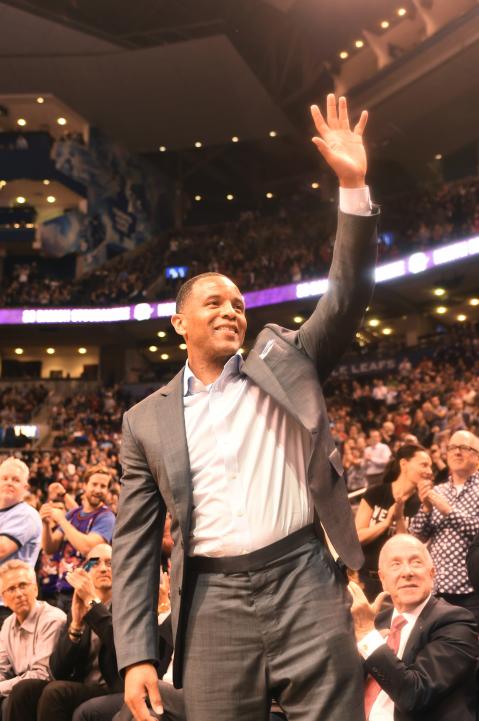

After playing in just 31 games for the San Antonio Spurs at the conclusion of the 2007-2008 season, Damon Stoudamire was aware of the obvious. He knew his playing career was finished, and the star guard was at a crossroads.

Like many NBA and WNBA players who hit the end of their playing careers, he had a conundrum: What do I do with all this time?

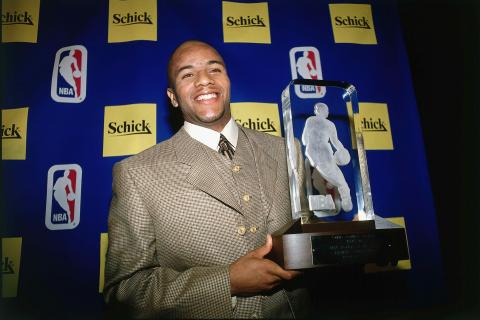

Stoudamire had felt it coming for several seasons, long after he won the 1996 Rookie of the Year Award. It happens to professional athletes in other sports, too. Since grade school, their days have been regimented by their sports schedule. There are workouts in the morning, practices in the daytime, weight training in the afternoons and games at night.

Suddenly, all that structure was gone, and Stoudamire needed something; he just did not know what.

“Athletes become creatures of habit. I was no different, but by my eighth year, I started to think about the end more than the beginning. I went back to Arizona and got my degree, and in my 10th year, I tore my patella tendon. I was 32, I had just signed a four-year deal, but it killed my momentum. I never really recovered from that injury. I still loved basketball, but you get older, and I had to admit some things to myself.

“So for me, I started to put my ego to the side. I never even turned in my retirement papers, but I knew I just couldn’t play anymore. I figured that out, and it was therapeutic. But still, athletes can get depressed. It is not enough for me to wake up and work out. Then it’s 10 a.m., and you still have a lot of time to burn.”