When the NBA’s All-Star Game finally came to Utah in 1993, Thurl Bailey couldn’t stay away. For a little over eight seasons, the goggles-sporting, athletic big man contributed to a Utah Jazz franchise that blossomed into a contender. Getting traded to the lowly Timberwolves in November 1991 may have been business, but it hurt. He was close to his teammates; Salt Lake City, an unlikely destination for a Black kid born in Washington, D.C., was home.

In 1999, Bailey returned to the Jazz after a stint playing in Europe. At his first home game, the fans greeted No. 41 with a standing ovation as he emerged from the tunnel. That wonderful last season made Bailey want to stay.

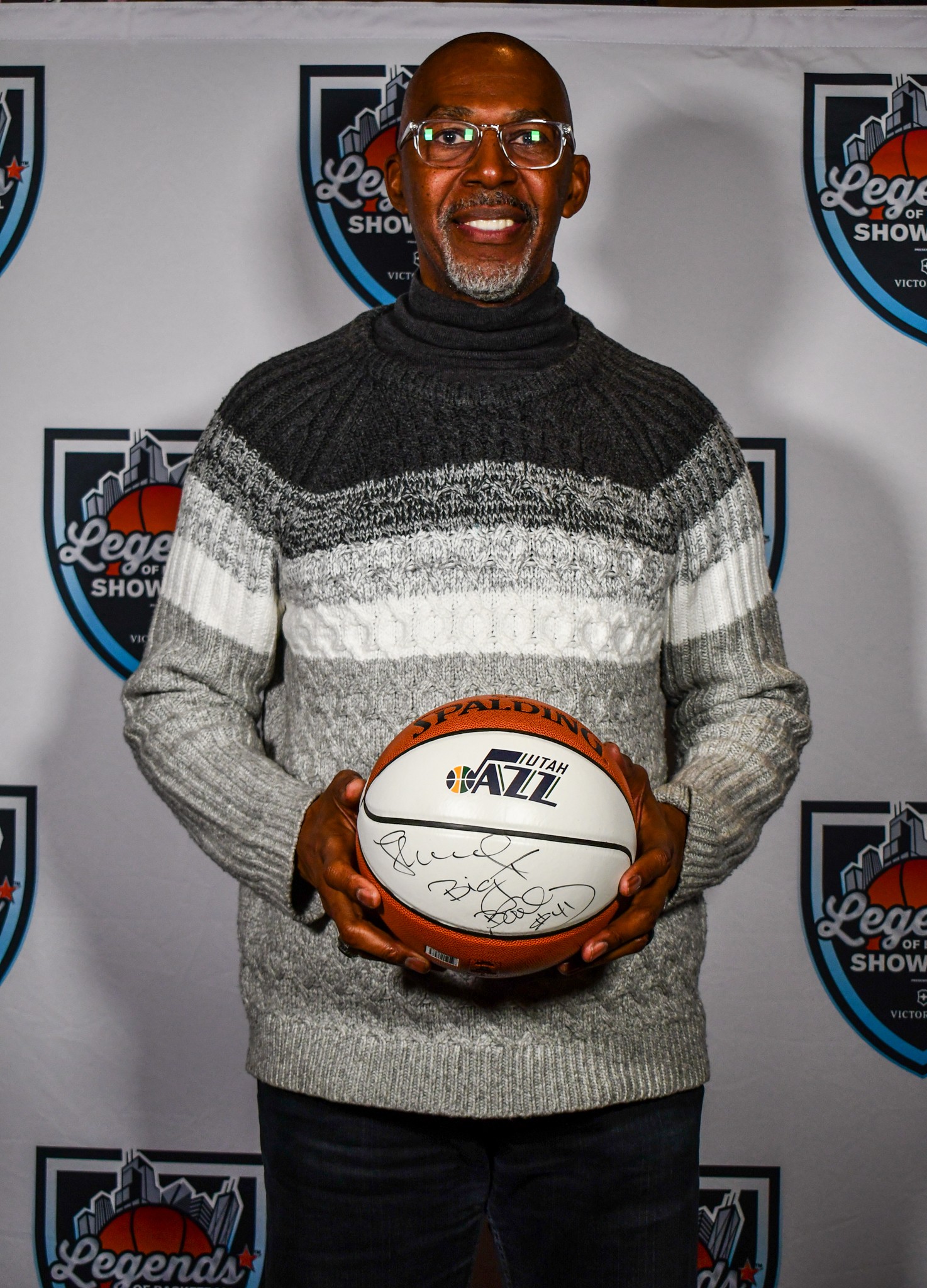

The All-Star Game’s return to Salt Lake City in February finds Bailey, the team’s longtime analyst, as an unofficial ambassador for the Jazz. He was part of the campaign to bring the game to the city, and his importance to the organization is such that in the wake of George Floyd’s death, the franchise sought his advice on how to handle the incident that shone a spotlight on America’s systemic racism.