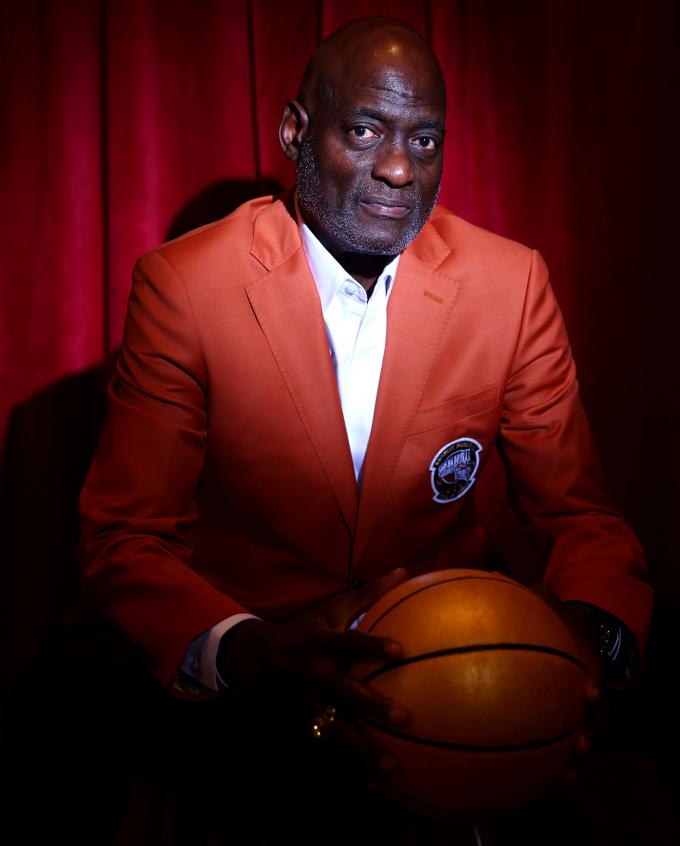

Michael Cooper is treating his Hall-of-Fame induction just like his Los Angeles Lakers glory days when he had to dismantle the NBA’s most potent offensive weapons.

He never took anything for granted back then, and Cooper isn’t about to take it easy now that he’s facing basketball immortality. While the induction ceremony is on October 13, his speech has been done since early September. Now, he’s watching game tape — speeches from prior inductees. On that day, his dome will be shaved. The suit will be immaculate. He’ll try not to cry…

And then, Cooper will run it back.

His enshrinement at the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame precedes another dizzying honor in January when the Lakers will send Cooper’s No. 21 jersey to the rafters. He will share space with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Jerry West, Elgin Baylor, Magic Johnson, Kobe Bryant, and Shaquille O’Neal among others — giants of the game, exemplars of a franchise synonymous with greatness.

Cooper never made an NBA All-Star team, which he says is typically a requirement for the Lakers to send a jersey skyward. That the franchise is breaking the rules “might be the ultimate show of love,” he says. It’s not surprising. As Cooper likes to say, he left a lot of blood, sweat, and skin on the Great Western Forum floor.